How Does the European Union Work?

- The modern European Union, founded in 1992, has its origins in post–World War II attempts to integrate European economies and prevent future conflicts.

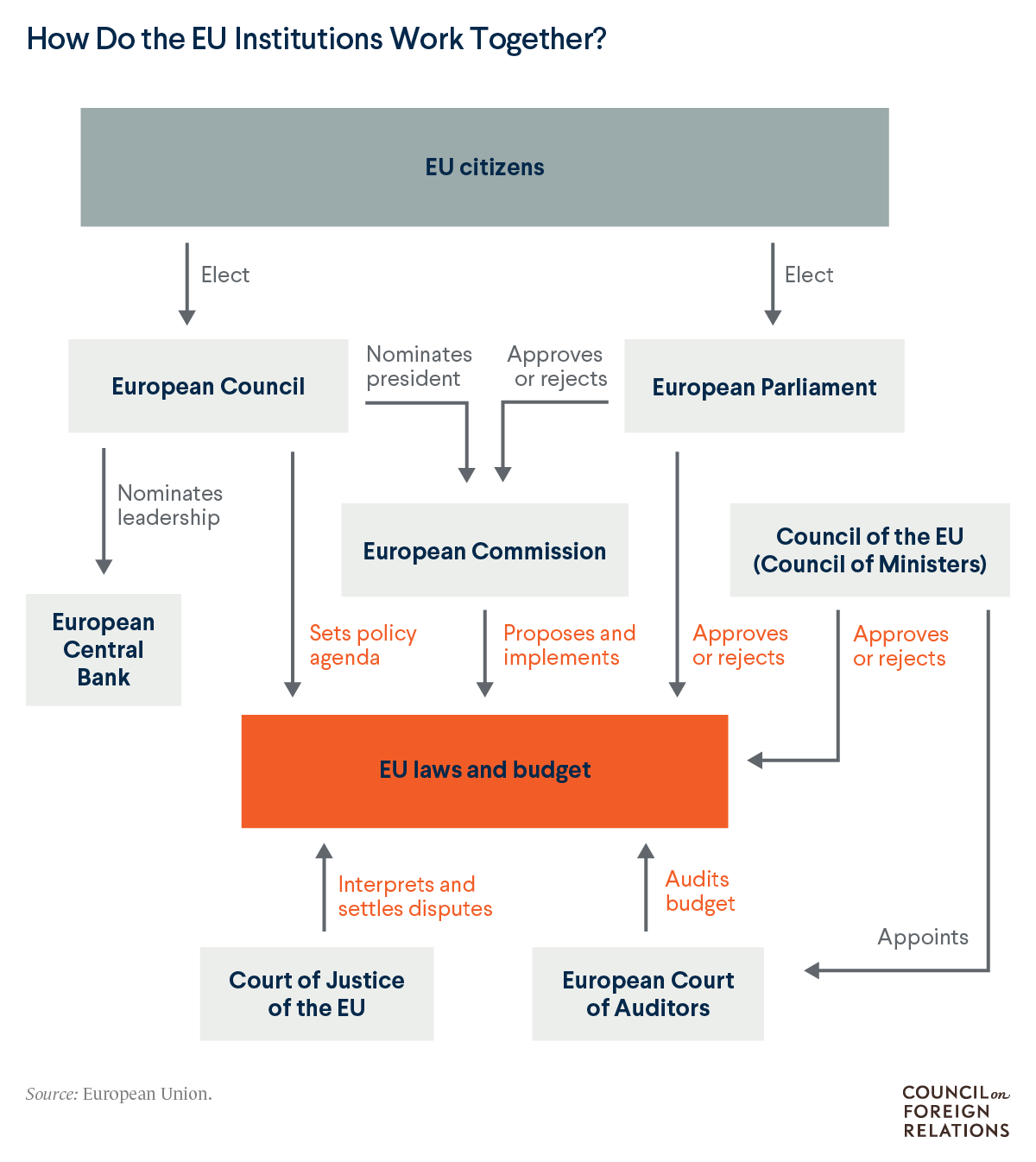

- It consists of seven major institutions and dozens of smaller bodies that make law, coordinate foreign affairs and trade, and manage a common budget.

- In recent years the EU has grappled with challenges to its unity, including Brexit, the ongoing refugee crisis, and disagreement over further integration.

Introduction

Since the end of World War II, European countries have sought to deepen their integration in pursuit of peace and economic growth. The institutions that became the European Union (EU) have steadily expanded and strengthened their authority as member states have passed more and more decision-making power to the union.

However, the EU has been buffeted by a series of crises in recent years that have tested its cohesion, including the 2008 global financial crisis, an influx of migrants from Africa and the Middle East, Brexit negotiations, and the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most recently, the bloc has scrambled to respond to aggression by Russian President Vladimir Putin, with tensions reaching a head in 2022 after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine created millions of refugees and threatened a broader war.

More on:

Today, the EU is a powerful player on the world stage, but the complexity of its many institutions can often confuse. Here’s a closer look at what the EU is and how it works.

What are the main institutions of the EU?

European integration began to take shape in the 1950s, but the modern union was founded in 1992 with the Maastricht Treaty. The EU was given its current structure and powers in 2007 with the Lisbon Treaty, also known as the Reform Treaty. Under these treaties, the bloc’s twenty-seven members agree to pool their sovereignty and delegate many decision-making powers to the EU.

There are seven official EU institutions, which can be roughly grouped by their executive, legislative, judicial, and financial functions.

The European Council, a grouping of the EU’s top political leaders, consists of the president or prime minister of every member state. Its summits set the union’s broad direction and settle urgent high-level questions. Its members elect a president, who can serve up to two two-and-a-half-year terms. The current president is former Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel.

More on:

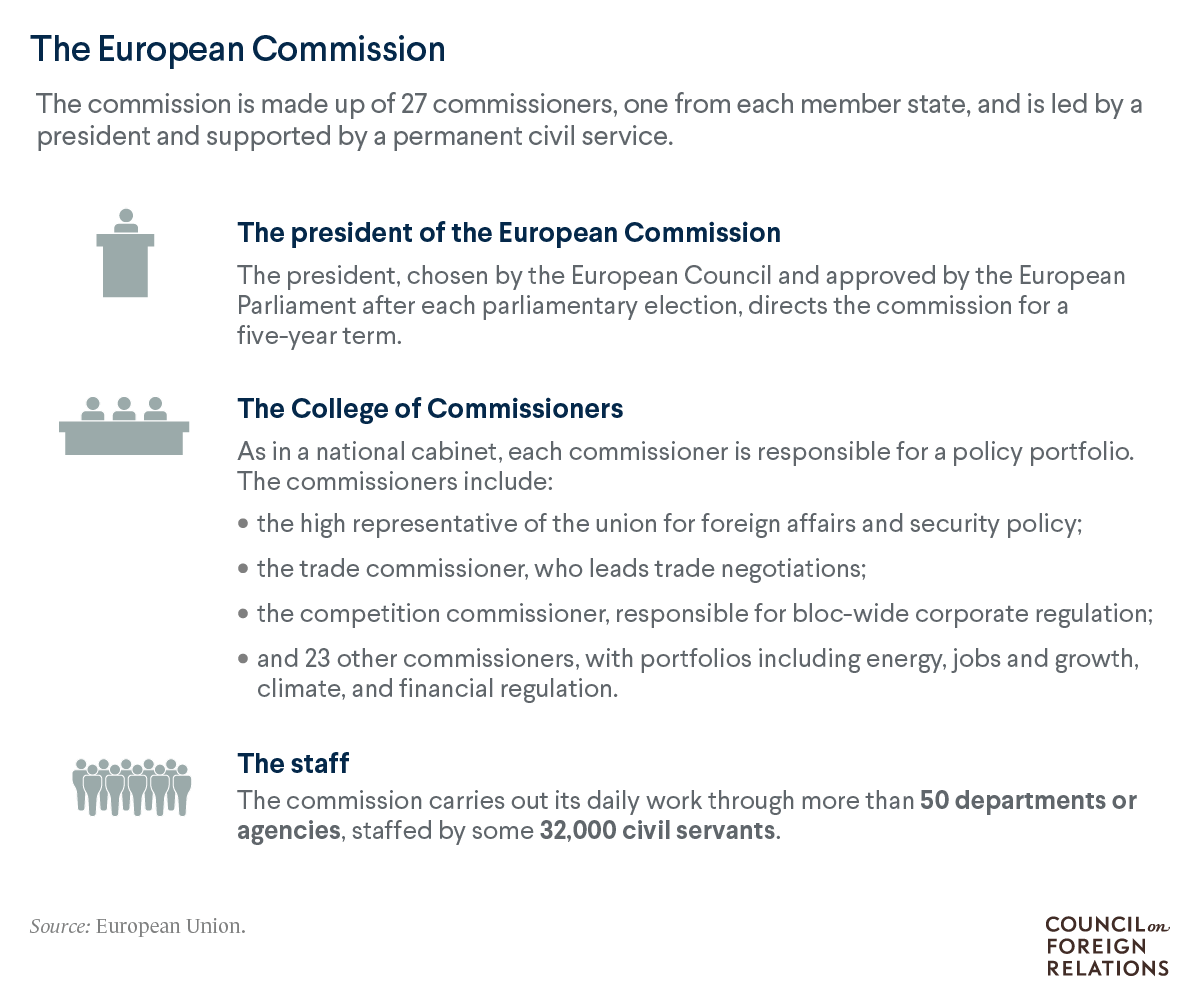

The European Commission, the EU’s primary executive body, wields the most day-to-day authority. It proposes laws, manages the budget, implements decisions, issues regulations, and represents the EU around the world at summits, in negotiations, and in international organizations. The members of the commission are appointed by the European Council and approved by the European Parliament. The current commission is led by former German Minister of Defense Ursula von der Leyen.

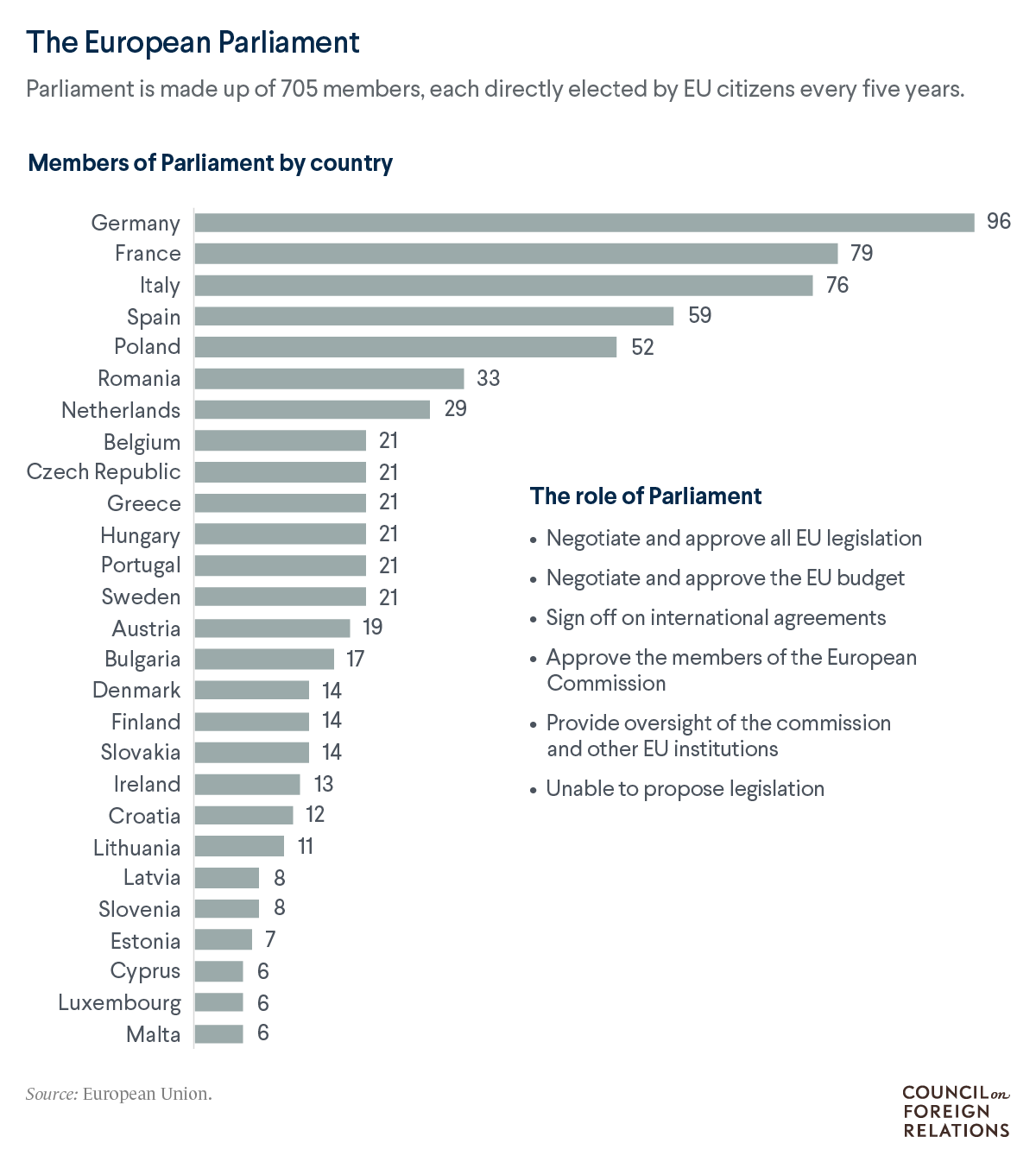

The European Parliament is the only directly elected EU body, with representatives apportioned by each member state’s population. Unlike traditional legislatures, it can’t propose legislation, but laws can’t pass without its approval. It also negotiates and approves the EU budget and oversees the commission. Parliament is currently led by Maltese politician Roberta Metsola.

The Council of the European Union, also known as the Council of Ministers to avoid confusion, is a second legislative branch whose approval is also needed for legislation to pass. This council consists of the government ministers from all EU members, organized by policy area. For instance, all EU members’ foreign ministers meet together in one group, their agriculture ministers in another, and so on.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is the EU’s highest judicial authority, interpreting EU law and settling disputes. The CJEU consists of the European Court of Justice, which clarifies EU law for national courts and rules on alleged member state violations, and the General Court, which hears a broad range of cases brought by individuals and organizations against EU institutions.

The European Central Bank (ECB) manages the euro for the nineteen countries that use the currency and implements the EU’s monetary policy. It also helps regulate the EU banking system. In the midst of the European debt crisis, which rocked the continent beginning in 2009, ECB President Mario Draghi controversially committed the bank to acting as a lender of last resort to ailing eurozone economies. French politician Christine Lagarde, former head of the International Monetary Fund, took over from Draghi in 2019.

The European Court of Auditors (ECA) audits the EU budget, checking that funds are properly spent and reporting any fraud to Parliament, the commission, and national governments.

The offices of these institutions are located across the EU, with headquarters in Brussels, Frankfurt, Luxembourg City, and Strasbourg.

How do the institutions relate to each other?

These EU institutions form a complex web of powers and mutual oversight.

At base they draw their democratic legitimacy from elections in two ways: First, the European Council, which sets the bloc’s overall political direction, is composed of democratically elected national leaders. Second, the European Parliament is composed of representatives—known as members of the European Parliament, or MEPs—who are directly elected by the citizens of each EU member state.

The European Council and Parliament together determine the composition of the European Commission—the council nominates its members and Parliament must approve them. The commission has the sole authority to propose EU laws and spending, but all EU legislation requires the approval of both Parliament and the Council of Ministers.

What are the powers of the European Parliament?

Although Parliament can’t initiate legislation, EU law can’t pass without Parliament’s approval. Parliament negotiates all laws, including the budget, with the commission and the Council of Ministers in an arrangement known as co-decision.

In addition, international agreements, including trade agreements, require Parliament’s sign-off. The president of Parliament, who is elected by the body, must also sign off on laws for their passage.

Parliament has a number of other powers. It approves members of the European Commission, meaning that parliamentary elections go far in determining the direction of EU policy. Parliament can also force the commission’s resignation. That has never happened, but on one occasion, in 1999, the commission resigned en masse over a corruption scandal before Parliament could act.

What does the European Commission do?

As the executive body, the commission is most responsible for the day-to-day operations of the EU.

The commission is tasked with drafting legislation and drawing up the EU budget. It sends these proposals to Parliament and the Council of Ministers and negotiates with them until it wins approval from both institutions.

The commission is also responsible for making sure EU laws are implemented and the budget is allocated correctly, whether through oversight of the member states or through one of the EU’s dozens of agencies.

Other duties include representing the EU in international organizations, promoting the bloc’s foreign policy, and leading trade negotiations. The commission also helps enforce EU treaties by raising legal disputes with the Court of Justice.

What does EU law cover?

Member states gave the EU different levels of authority over different areas, known as competencies:

- Exclusive competencies are areas in which only the EU, not national governments, can pass laws. These include many of the core activities of the EU, including the customs union, business competition rules, trade agreements, and, for eurozone countries, monetary policy.

- Shared competencies are those in which national governments can legislate, but only if the EU doesn’t already have related laws. This applies to the single market, which provides for the free movement of goods, services, people, and capital. It also applies to agriculture, regional development spending, transportation, energy, environmental and consumer protections, public health, and research and technology.

- Supporting competencies are areas in which the EU can only bolster activities that have already been undertaken by member states. They include culture, education, sport, and many social policies.

How does the EU run its foreign policy?

The common foreign and security policy (CFSP), as the EU’s foreign policy is known, primarily concerns diplomacy, security, and defense cooperation.

High-level direction is set by the bloc’s national governments through the European Council and the Council of Ministers. But CFSP decisions must be unanimous, and member states remain free to make their own foreign policies. This has led to criticisms that the EU’s ability to put forward a common stance is often undermined by divisions between member states.

Implementation of the CFSP, the responsibility of the European Commission, is carried out by the high representative of the union for foreign affairs and security policy, a position informally known as the EU foreign minister. This position, currently held by Spanish politician Josep Borrell, was created by the Lisbon Treaty to strengthen and centralize EU diplomacy.

The treaty also created an EU diplomatic service, the European External Action Service. It is managed by the commission, draws staff from across the EU institutions, and operates in more than 140 countries.

The EU’s unity on foreign policy has been repeatedly tested in recent years. The bloc played a leading role in negotiating international agreements including the Paris climate accord and the Iranian nuclear deal, both finalized in 2015. In 2016, it reached a deal with Turkey to limit refugee admissions, but migration policy has deeply divided members. It also helped create the conditions for Brexit, the departure of the United Kingdom (UK) from the union. In major conflict zones, such as Libya and Syria, the bloc has struggled to define a common policy.

Relations with Russia have emerged as a central issue for the bloc, with President Putin citing EU and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) expansion as justification for his aggressive moves in the Caucasus and Ukraine. The EU had imposed sanctions in the wake of Putin’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, but members remained divided over how closely to work with Moscow on energy and other areas given the bloc’s dependence on Russian oil and gas. That calculus shifted with Russia’s 2022 war against Ukraine, which prompted Germany to halt a major Russian gas pipeline project, Nord Stream 2, and led to more intense EU sanctions on Russian financial institutions and individuals, including Putin himself. Member states also quickly mobilized to welcome millions of refugees from Ukraine.

Meanwhile, debates over both deeper integration and EU expansion have continued. France and Germany in particular have differed over the future of EU institutions, while efforts to incorporate new members in the Balkans have largely stalled. Divisions have also arisen over investments in critical infrastructure by companies such as Huawei and other Chinese firms.

How are trade negotiations handled?

The EU foreign ministry is distinct from the EU’s common commercial policy, which carries out trade policy via the EU trade commissioner. National governments have agreed to transfer all their decision-making power in this area, unlike other foreign policy matters, to the EU.

The EU needs a unified trade policy because of its customs union, which sets a single external tariff for the entire bloc, and its single market, which treats all goods and services that enter the EU the same. Thus, the EU acts as one body in trade negotiations and at the World Trade Organization.

Completing a trade agreement requires most of the EU’s institutions.

- First, national governments, through the European Council and the Council of Ministers, must agree to give the European Commission a mandate to negotiate with a specific partner.

- The EU’s trade commissioner then takes the lead and negotiates a deal.

- Before any deal can be signed, it must be approved by the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers, like any other legislation.

Finally, if a trade deal is particularly broad, it may also require the individual approval of each EU member state. The EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) is one such example. Signed in 2016, CETA has yet to take full effect because the Italian government has so far refused to sign off on it. The EU was also in the midst of negotiating a comprehensive trade pact with the United States, known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), but the deal was shelved under U.S. President Donald Trump, who called the EU a “foe” on trade.

Is there an EU military?

EU countries cooperate on military missions, but they are conducted on a voluntary, case-by-case basis by national militaries. There is no standing EU army independent of member states’ armies.

EU security efforts take place under the common security and defense policy (CSDP), which is also operated out of the European Commission and led by the EU foreign minister. The CSDP involves both military and civilian work, ranging from police training programs to peacekeeping, anti-piracy, and rescue missions. The EU’s current major military missions are all in Africa, including in Mali, Niger, South Sudan, and the Horn of Africa.

Still, EU military operations have raised the question of how they relate to the NATO military alliance, whose membership partially overlaps with the EU’s. The Lisbon Treaty recognizes NATO as Europe’s primary means of collective defense and specifies that the EU will play a supporting role. French President Emmanuel Macron, however, has become the continent’s leading advocate for the creation of an EU army, part of a vision for what he calls “strategic autonomy” to reduce Europe’s dependence on the United States.

Macron’s ideas, as well as Washington’s long-standing demands that EU countries increase defense spending, made little headway before 2022. But Russia’s war in Ukraine has promised to upend much of the EU defense status quo: Germany reversed decades of policy with pledges to double its military budget, while the EU used its own budget to finance weapons transfers to Ukraine. France has seized on the crisis to assert European leadership, with Macron spearheading talks with Russia. In addition, EU foreign minister Borrell says the situation underscores that it is time for the EU to “take more responsibility in terms of defense policy.”

How big is the EU budget?

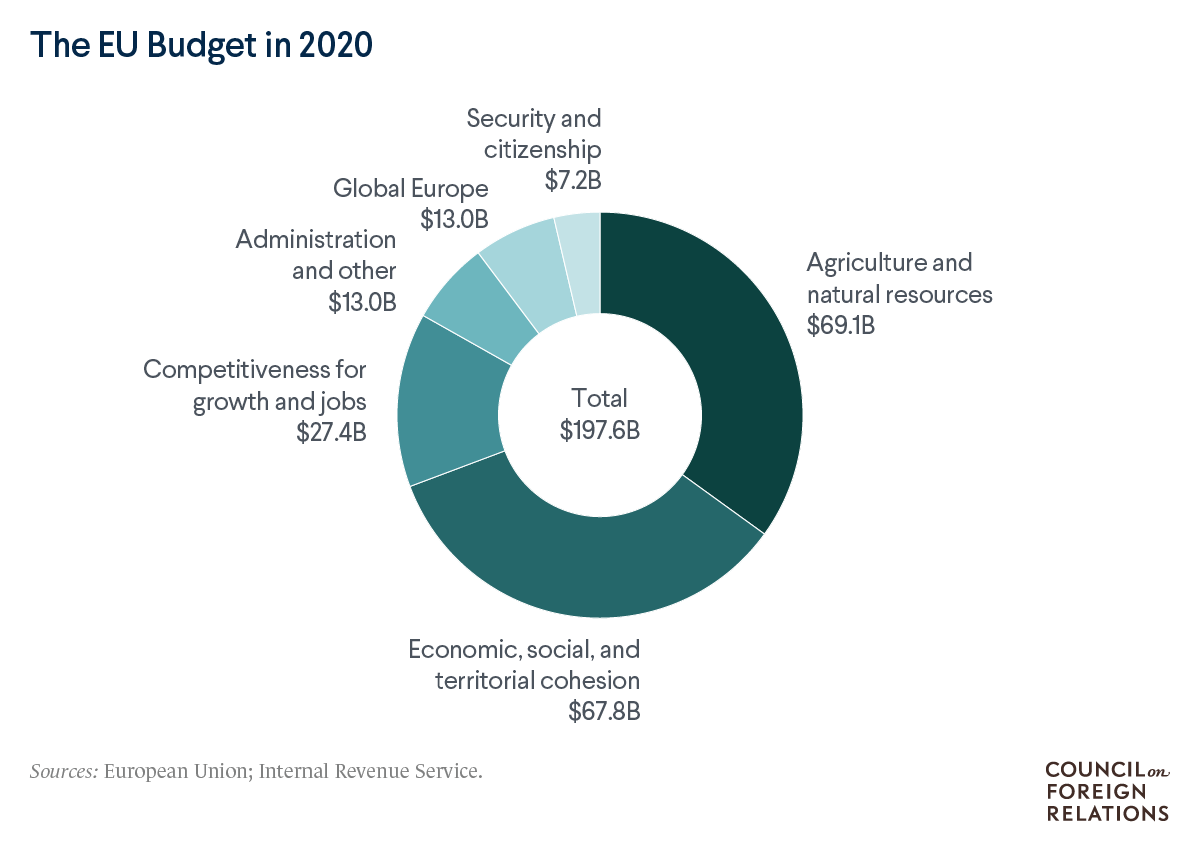

The European Union’s spending was a little more than $197 billion in 2020, the last year for which the European Commission released its full accounting.

- One of the largest chunks, at about 35 percent, is spent on agricultural programs. The biggest outlays are for direct payments to farmers and the development of fisheries, forests, and rural communities.

- An equal share goes to economic, social, and territorial cohesion, meant to help the EU’s less developed countries catch up. The spending covers investments and technical assistance for small businesses, infrastructure development, jobs programs, and low-carbon energy.

- Related spending on competitiveness, about 14 percent, goes to EU-wide research and development, energy, transportation, and telecom initiatives.

- Global Europe covers the EU’s foreign policy efforts, while security and citizenship focuses largely on migration and law-enforcement programs.

The EU budget, while renegotiated by the European Commission, Parliament, and the Council of Ministers yearly, must fit previously agreed budget frameworks that set a cap on total spending, generally over a seven-year time span.

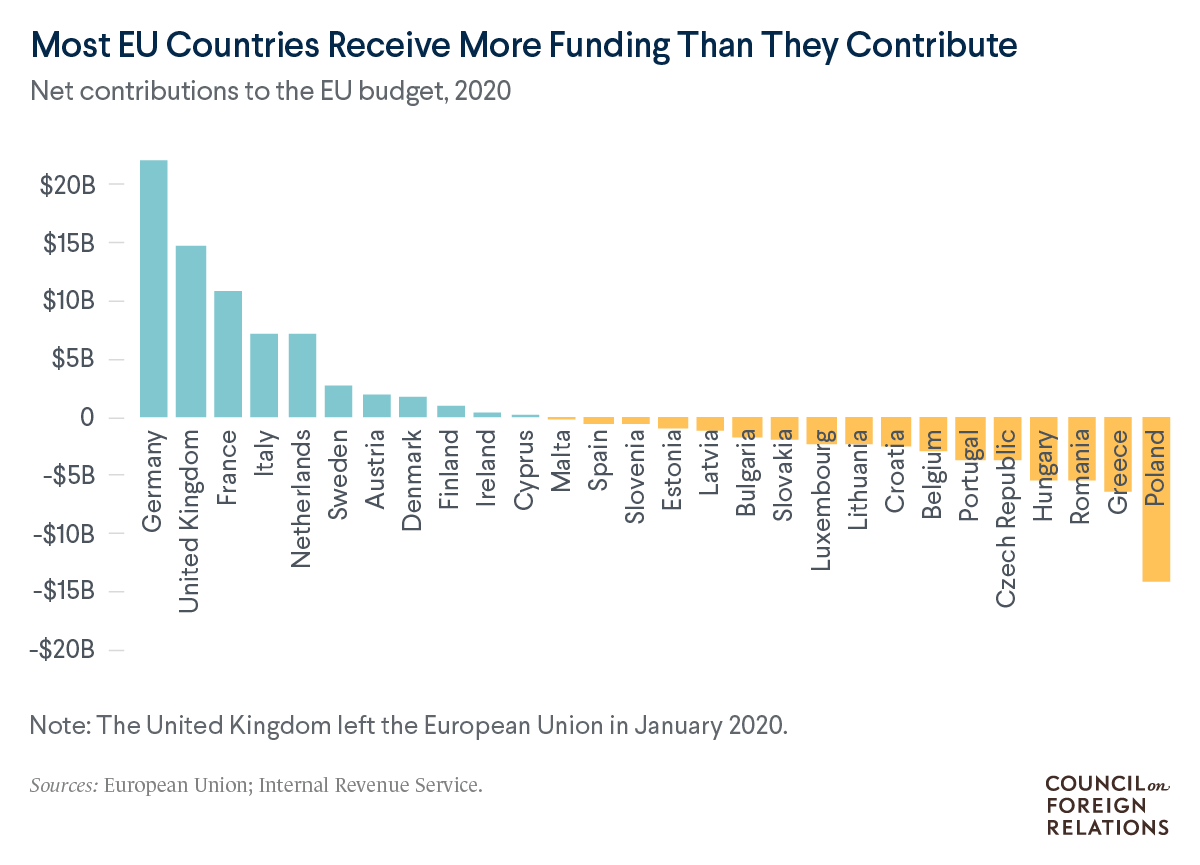

The EU budget must balance, since the bloc has no authority to spend more than it takes in. Almost all of its revenue comes from member states, which contribute varying amounts based on their economic heft. Many less developed states are net beneficiaries, receiving more in EU funding than they pay.

In 2020, Poland was the greatest net beneficiary, receiving $14 billion more than it paid in, followed by Greece, Romania, and Hungary, each at more than $5 billion.

What about the EU’s other organizations?

In addition to the EU’s seven official institutions, the bloc has dozens of other bodies—agencies, committees, offices, foundations, schools, and banks. They generally do research, make recommendations, carry out administrative tasks, or otherwise help implement EU policy. There are also political and economic arrangements that include some but not all EU countries.

Some major examples are:

- The Schengen Area comprises countries that have agreed to eliminate all border controls between them and strengthen law-enforcement cooperation. Its membership includes four non-EU countries—Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland—while five EU countries—Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland, and Romania—don’t participate.

- The eurozone is the group of nineteen of the twenty-seven EU members that use the euro currency. Their monetary policy is subject to the European Central Bank, which issues and manages the euro. Denmark and the UK were given permanent exemptions; the rest of the EU is legally required to join the eurozone at some point.

-

The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is an EU agency that provides emergency loans directly to struggling governments or private banks, conditional on economic reforms, a role the ECB has sought to avoid. Established in 2012, it is the permanent incarnation of a series of temporary bailout funds created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. It has once again taken center stage during the coronavirus pandemic as policymakers have pledged hundreds of billions of dollars of additional lending through the ESM.

-

The European Investment Bank (EIB), founded in 1958, is the EU’s official investment bank, issuing low-cost loans, equity investments, and other financing to thousands of businesses, government programs, and other initiatives. Its shareholders are the twenty-seven EU member states. The vast majority of its investments are focused on projects that advance the EU’s economic and social goals, including financing for small businesses, energy systems, infrastructure, and programs that promote gender equality and environmental sustainability. However, the bank also funds projects in other regions of the world.

- The European Economic Area (EEA) is a 1994 agreement extending the EU single market to three non-EU countries: Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway. Those three countries, plus Switzerland, form the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), a separate free trade area.

Finally, several other bodies that operate in or are based in Europe are often incorrectly assumed to be EU institutions.

- The Council of Europe is an international organization based in France whose mission is to promote democracy and human rights in Europe. Its forty-seven members include many non-EU countries, including Russia and Turkey.

- The European Court of Human Rights, part of the Council of Europe, exists to enforce the European Convention on Human Rights, an international agreement on civil and political rights that entered into force in 1953.

-

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), headquartered in London, was founded to help countries of the former Soviet Eastern Bloc transition to capitalist economies. The bank now has more than seventy members and operates around the world, including in Africa and Asia.

- The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) is an international body whose membership includes much of Europe, Russia and other post-Soviet states, and the United States and Canada. Formed during the Cold War, its mission is to strengthen East-West cooperation on arms control, conflict management, law enforcement, and other security issues.

- Interpol, a network of police agencies from 194 countries, is based in France. It grew out of previous cooperative law-enforcement efforts by mostly European countries but now has a worldwide remit.

Online Store

Online Store