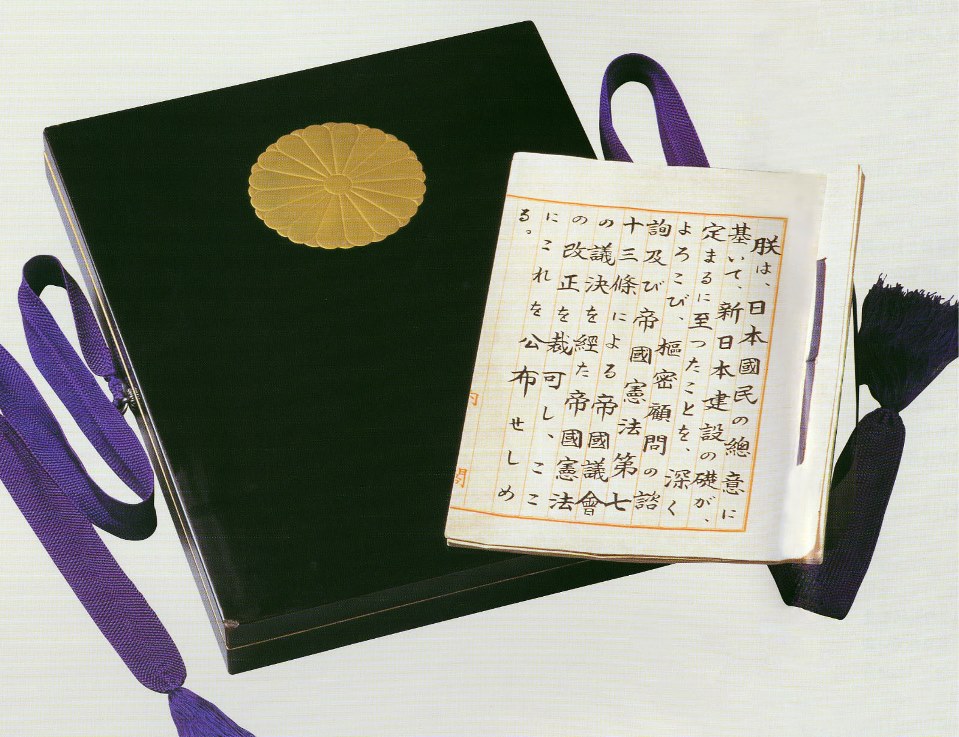

For over seventy years, Japan’s constitution has remained untouched, a symbol of a reformed nation and a democratic society.

Introduced under U.S.-led occupation in the wake of World War II, Japan’s postwar constitution presented a unique promise: that the Japanese people will never again resort to war to solve international disputes.

The 1947 constitution transformed the lives of Japanese citizens, changing the role of the emperor, diminishing the power of the military, and creating new rights for women.

Today, as democratic practice has come under scrutiny around the world, Japanese citizens too are deliberating how effectively their government works.

Multiple challenges are prompting calls for reform. Japan’s aging population threatens its economic vibrancy. Repeated natural disasters highlight the need for better emergency management, as well as policies to adapt to climate change. The growing military power of Japan’s neighbors raises questions about the country’s defenses. New technologies also raise questions about privacy and citizen access to information.

Japan’s constitutional debate is about not simply the document’s past but also the nation’s ability to respond to these twenty-first-century challenges.

Debate over the constitution is not new: for much of the early postwar period, the Japanese were divided over the 1947 constitution. Some welcomed it as Japan’s "peace constitution," while others decried it as "MacArthur’s constitution."

The future of Japan was a source of contention among the Allied powers as they began to consider the new postwar order. Within Japan, too, opinions varied over how to reform and rebuild in the wake of Japan’s catastrophic defeat.

Once adopted in 1947, the constitution became a symbol of transformation for Japan, a commitment to a brighter, more peaceful future.

Since its formation in 1955, the Liberal Democratic Party has advocated for rewriting the constitution.

In the 1990s, political realignment brought new parties and new ideas to the debate over constitutional revision. These forces gained influence in the Japanese parliament, while those parties opposed to any amendment waned.

Business and the media too pushed for change.

Today, almost all of Japan’s political parties have put forward their thinking on how to improve the constitution in their policy platforms, yet they differ on the issues.

The proposals for amendment have increasingly focused on governance reform rather than on restoring prewar practices and institutions.

While Japan’s politicians are less reticent about amending the constitution, the Japanese public remains cautious.

Politicians moved ahead with parliamentary deliberations on the constitution in the early 2000s, opening broader debate within Japan on the pros and cons of revision.

Roughly half of the Japanese public say they are willing to revise the constitution, but the Abe cabinet’s recent proposals faltered.

Politicians, scholars, and activists alike have joined the conversation, revealing an appetite for debate but no consensus on what to amend.