In Latin America, Your Zip Code—Not Just Your Nationality—Determines Whether You Live in a Democracy

Many big cities are doing well, but in flyover country organized crime and corruption often smother democracy.

July 9, 2024 3:44 pm (EST)

- Article

- Current political and economic issues succinctly explained.

Panic over democratic backsliding in Latin America often brushes past the good news: the vast majority (about 9 in 10) of the region’s 650 million people still live in democratic countries.

The bigger, overlooked issue is that millions of these same people do not live in democratic towns, cities, or states.

More on:

Outside the region’s big cosmopolitan cities, many live in zones dominated by mafias and corruption networks. Mayors and governors aligned with these interests may not be able to do much damage beyond city or state lines, but within them, they can be as repressive as any of the region’s dictators, past or present. In extreme cases, they have built mafia states in miniature.

And the gap is only widening. As many of the region’s vibrant metropolises (often capital cities) have pulled ahead over the past two to three decades—becoming more democratic, and often better governed—many smaller towns and cities have moved in the opposite direction.

That is the biggest risk to the region’s democracies today: not autocratic presidents who successfully dismantle democracy from the top-down—those are rare—but local tyrants who corrode democracy at its foundations.

Sometimes democratic erosion is halted through strengthening checks and balances and constraining power. But this problem requires a different fix: national governments that know how to use power to discipline local despots and make the local state more responsible and responsive. If no action is taken, Latin America’s democracy gap between metropolises and the rest will only grow.

How (Local) Democracies Die

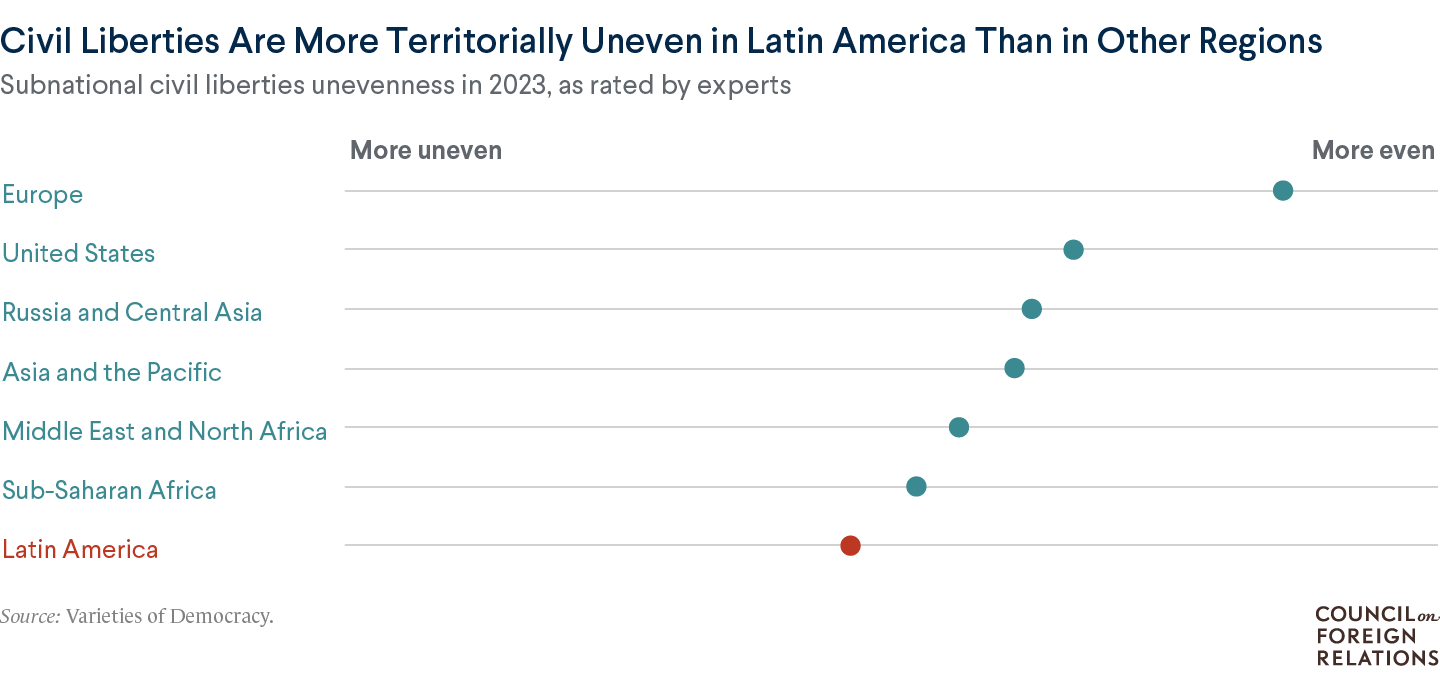

When it comes to guaranteeing civil liberties, Latin American democracies are among the most territorially uneven in the world, according to data from the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem). What rights you have, in practice, often depends on where you live.

More on:

There is no clearer example than Mexico. Last month, I traveled to the country before its June 2 general elections. In Mexico City, I saw democracy at work. Both camps (the governing party and the opposition coalition) held packed public rallies. Journalists published hard-hitting stories about governing party and opposition candidates up until the last minute.

I struck up conversations with voters in neighborhoods that ran the socioeconomic gamut. Almost no one was nervous to talk politics or tell me how they planned to vote. When results rolled in, the opposition did less well than in the past, but still held onto several important boroughs. Mexico City—like Bogota, Sao Paulo, and several other large, globally connected regional cities—is a democratic, pluralistic place, especially when you compare it with its own past. Chances are it will stay that way.

But when I drove an hour to Mexico City’s south, crossing state lines into Morelos, I entered a parallel universe. There, candidates are elected, but the mafias govern. Sixteen different criminal groups have carved out territorial footholds in the state, profiting from drug trafficking, kidnapping, illegal logging, fuel theft, and extortion. At best, mayors and state government officials in Morelos act as passive bystanders to the predation. At worst, they are its accomplices. In some towns, the gangsters and city hall are one and the same.

Morelos’ mafias weren’t passive spectators in the lead up to voting day. They were its most engaged participants, financing candidates, supplying some with teams of gunmen, intimidating and killing others, and posting roadside banners with instructions to voters. One such banner was tellingly signed, “the ones in control.” Even deciphering which candidates are tied to which mafias is a challenge. Local journalists practice routine self-censorship. It’s not because they want to, several told me, but because their lives depend on it. There might be voting in a place like Morelos, but there is no democracy—at least not in any meaningful sense of the word.

There is a Morelos in almost every Latin American country—usually, more than one. It’s not always violent criminals running the show. Sometimes, local politicians drive democratic erosion. Take Barranquilla, Colombia’s fourth-most populous city. For nearly twenty years, the Char family (one of Colombia’s richest) and their close political allies have held city hall and often also the governorship.

The Char win elections by large margins. They are genuinely popular. They are not like the gangster mayors of Morelos, except in one way. They, too, tilt the playing field—not with guns, as I found through dozens of interviews with Barranquilla residents and a member of the Char family in 2019, but by doling out public contracts, allegedly buying votes, and quietly pressuring critics. Dozens of criminal investigations into the family remain open but perpetually frozen in Colombia’s justice system. One, by Colombia’s Supreme Court, landed a family member and ex-senator in jail last fall (he has since been freed by habeas corpus, but the investigation continues).

Across Latin America, millions of people live under these conditions—ruled by criminal-political mafias like those of Morelos or domineering cliques like the one installed in Barranquilla. They might live near cities with thriving democracies. But when it comes to the freedoms they enjoy in their own communities, they might as well live a world away. Such is life in a spectacularly uneven democracy.

To Defend Democracy, Finish Democratization

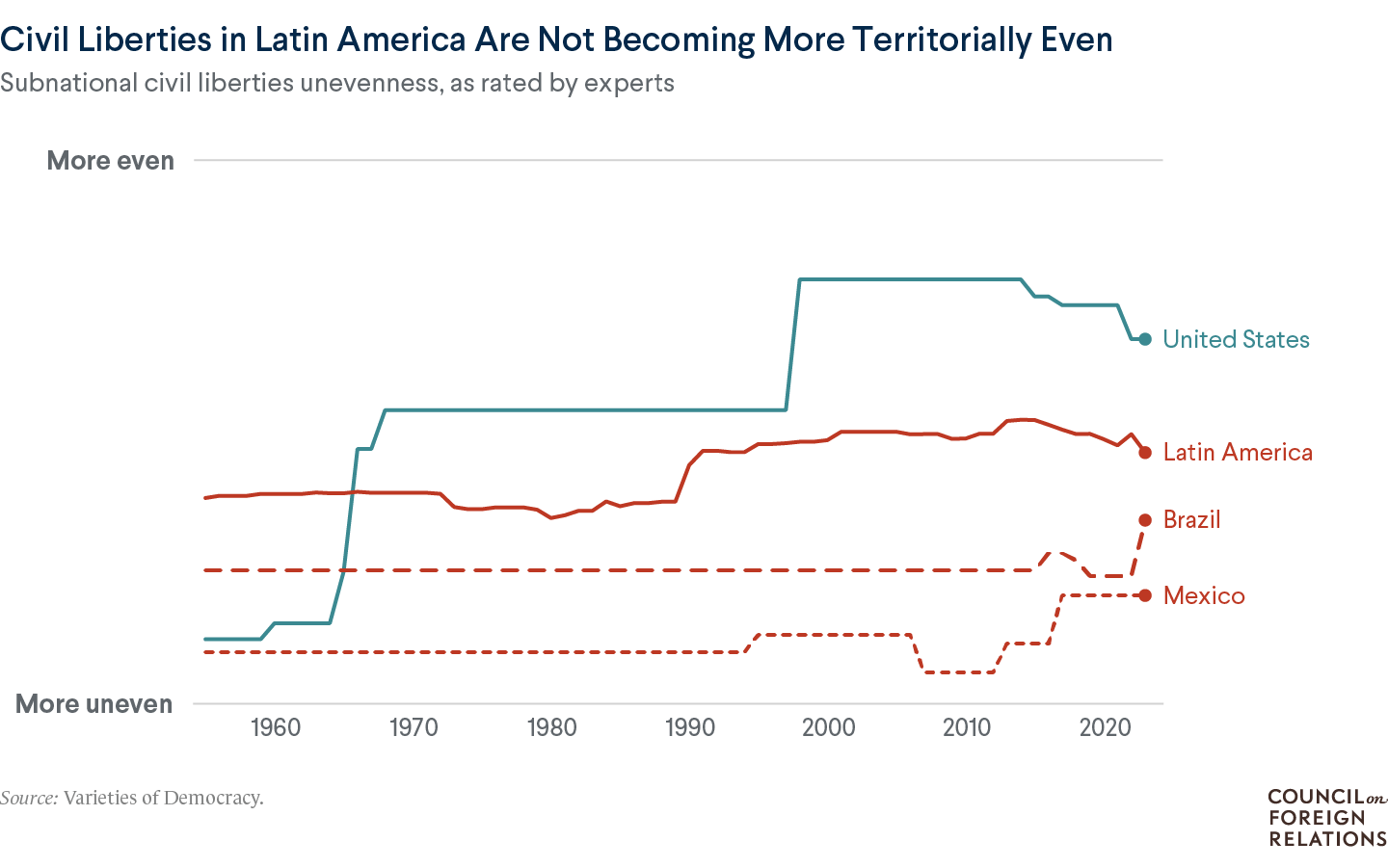

Uneven access to civil liberties isn’t a uniquely Latin American problem. It’s a feature of most democracies around the world. Historically, the United States was among the worst offenders. Many southern states were their own authoritarian enclaves of single-party rule and brutal repression from the end of Reconstruction until the end of Jim Crow. Then came the civil rights movement, which at last helped bring democracy to the south. From the 1960s on, V-Dem data shows, the United States gradually flattened out access to civil liberties and political rights across its national territory, even if some unevenness persists to this day.

Latin American countries also evened out their democracies, but much more slowly. And by the 2000s, the progress toward extending civil liberties and rights into less-than-democratic enclaves all but stopped. The risk now is that things stay that way or get worse. Given the growing territorial presence of organized crime groups in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and other countries, it’s a real possibility.

The region has a playbook for stopping would-be autocratic presidents: build and exercise checks and balances. In countries like Brazil in recent years and Colombia in the 2000s, the guardrails have largely held. But there is no playbook for reining in autocratic, mafia-linked governors and mayors. Political scientists have studied how and why democracies do away with their authoritarian enclaves. It helps when local opposition gets organized, local economies diversify, and national governments hold abusive local officials accountable.

This gives Latin America some reason for hope. The region is full of cases of courageous local opposition organizing, even under the toughest possible circumstances. Take the case of Nayarit, a small state on Mexico’s Pacific coast. Local leaders organized a truth commission in 2017 to expose an ex-governor and state prosecutor for extorting, torturing, and disappearing hundreds of people. More than two thousand people came forward to participate. If opposition can organize under those conditions, it can organize anywhere.

The bigger issue is generating the political will at the national level to match. Presidents of Latin American democracies have a habit of ignoring, and even protecting, local tyrants as long as they drum up votes for the governing party (again, something that occurred routinely in the United States in the twentieth century).

Consider Mexico, where President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, commonly known as AMLO, has recruited governors accused of colluding with organized crime to his party. AMLO’s predecessors in the presidency did the same, but he has taken the practice to a new level, swelling his party’s ranks in the process. Some claim AMLO has damaged Mexican democracy by centralizing too much power in the presidency. Arguably, he has done more damage by giving too much power away to abusive and corrupt governors. It’s not a problem unique to Mexico. Tolerating local mafias and their political allies might be unseemly, but in the short term, it’s often politically rational. Only Latin American presidents who perceive the long-term downsides—the violence, instability, and out-migration that local tyrannies foster—will find the motivation to make a change.

That’s the political will problem. But there’s another hurdle Latin America will need to clear to even out its democracies: increasing local state capacity. Even if presidents and judiciaries discipline abusive local officials, the weakness of state institutions at the local level, and the scarcity of alternative sources of campaign finance, encourages mayors and governors to turn to corruption rings and crime. Latin America’s states are not weak everywhere or along every dimension, but at the local level, they need strengthening. Institutions that oversee public procurement and infrastructure, the prosecution of crime, and education and health need the biggest upgrade.

There is still good news. In many of Latin America’s metropolises, democracy is surviving and even thriving. In a few countries—Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay—local politics already operates democratically pretty much everywhere. But elsewhere, local rule by mafias and corruption rings is on the rise. Left unchecked, it could sap the impressive resilience of the region’s democracies. Ensuring there are the conditions for democracy to thrive everywhere—and not just in metropolises—is the challenge ahead.

This publication is part of the Diamonstein-Spielvogel Project on the Future of Democracy.

Online Store

Online Store