Pivotal Elections for France—and Europe

French President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist government faces a resounding defeat in snap legislative elections, potentially creating a wave of turbulence in one of the European Union’s founding member states.

June 27, 2024 5:34 pm (EST)

- Expert Brief

- CFR scholars provide expert analysis and commentary on international issues.

French President Emmanuel Macron has called snap legislative elections for June 30 and July 7 after the dismal results for his centrist movement, Renaissance, during the elections for the European Parliament earlier this month. Macron’s move is shaping up to be a rather irresponsible gamble that could plunge France into political, social, and economic turmoil, with repercussions across Europe.

What will the elections decide?

All 577 seats in France’s National Assembly are being contested, and hence 289 seats are needed for a majority. In the outgoing assembly, Macron’s government allies control around 245 seats, with leftist parties holding 131 seats, the far-right 89 seats, and the center-right Republicans 61.

More on:

Each seat in the National Assembly is basically its own race, which makes the exact outcome hard to predict, as local idiosyncrasies in France’s multiparty democracy can play an important role. A candidate needs 50 percent of the vote to win in the first round. If no one surpasses that threshold, all candidates who receive votes from at least 12.5 percent of the registered voters will qualify for the second round, in which the candidate with the most votes wins. In other words, electoral turnout is crucial, as a turnout of about 50 percent usually means that only the top two candidates will make it to the July 7 runoff. It is rare for more than three candidates to get more than 25 percent of the actual vote. Three-way contests can and have taken place, though the second round usually ends up being a straightforward battle between left and right.

What is at stake for France in these elections?

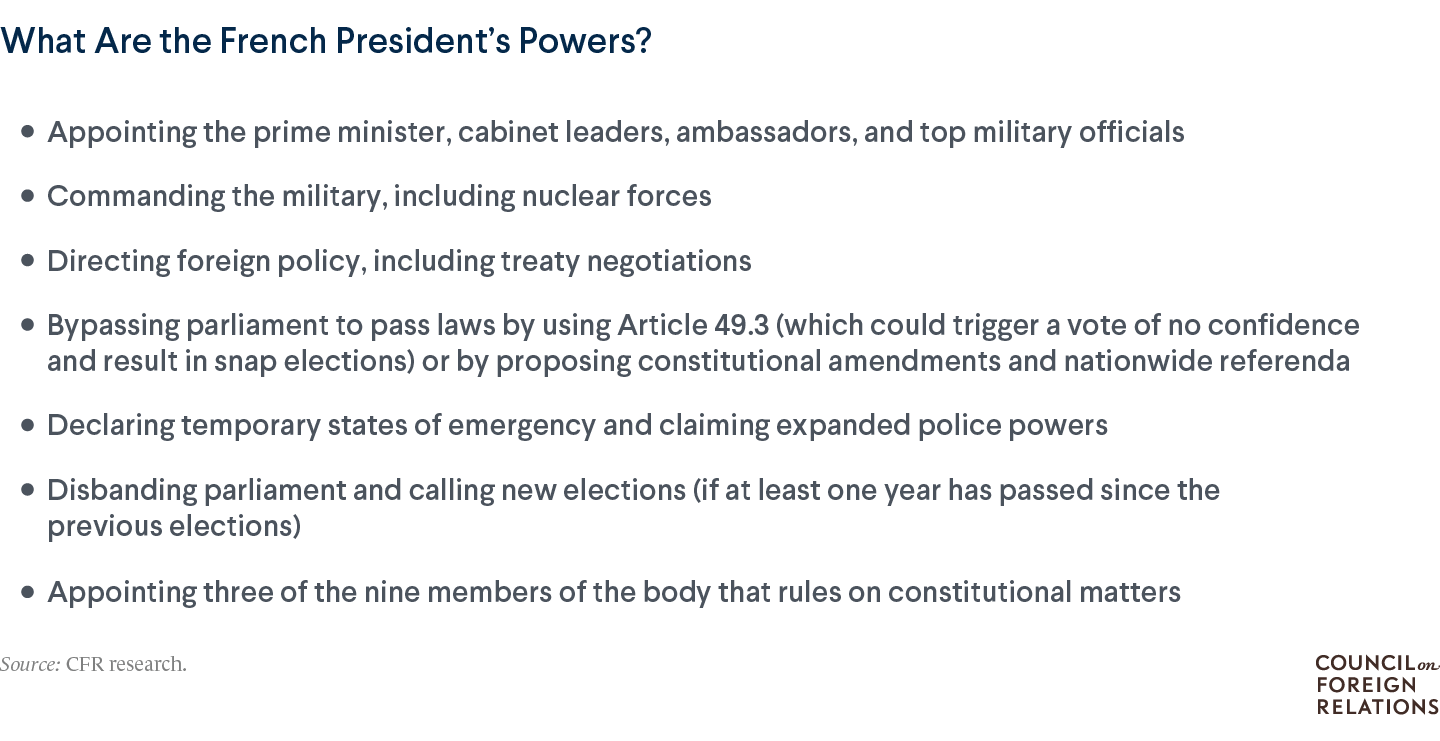

The governability—and stability—of France over the next three years is at issue. A potential parliamentary majority for the far-right National Rally party would force Macron, whose term ends in 2027, into a difficult “cohabitation” with Jordan Bardella, who seeks to become prime minister. Bardella is the twenty-eight-year-old, charismatic deputy and protégé of Marine Le Pen. The latter is preparing to run for president for a fourth consecutive time in 2027. There is a division of labor between president and prime minister in France, with the former having the monopoly over foreign policy and the latter over domestic policy. But the two can frustrate each other’s plans a great deal; Macron could decide to veto legislation passed in the National Assembly, or Bardella’s government could decide not to implement certain presidential decrees as the far-right would control all government ministries. This could result in constant gridlock at best and a constitutional crisis at worst. For example, while Macron could decide to send new weapons to Ukraine to support Kyiv in its war against Russia, Bardella could slow down delivery or raise all kinds of bureaucratic hurdles against its implementation.

Additionally, both the left-wing New Popular Front and the right-wing National Rally are proposing radical changes on economic and social policy, immigration, and the environment, some of which could be incompatible with the current framework of European Union (EU) law. In effect, many of Macron’s reforms—such as increasing the retirement age from sixty-two to sixty-four, efforts to reduce the budget deficit through spending cuts or tax increases, and policies to switch to renewable energy and fight climate change—could be undone by a new government. A far-right or far-left government could also trigger a new wave of street protests and fan the flames of social unrest. Macron had vowed to end both the left and the right as we knew it while running for president in 2017. On June 9, he decided to call the far right’s bluff about daring him to dissolve parliament and initiate fresh legislative elections, by doing exactly that. Macron gambled it would result in a reinvigorated centrist majority for his government given the much higher stakes of national elections compared to EU elections. But he may have inadvertently brought left and right back to life, while his centrist politics is imploding under the weight of anti-incumbent sentiment.

What about the rest of Europe?

With the current German government in disarray—Chancellor Olaf Scholz’ governing coalition also got a shellacking from voters during the EU elections, and it faces difficult budget discussions ahead in the summer and fall—the fact that France could be facing prolonged governmental gridlock is very bad news for the Franco-German engine of European integration, and hence bad for Europe’s future. While EU institutions are preparing for a transition of power themselves this fall, the EU will need strong support from key member states, especially France, to tackle the challenges it will face in the next five years. These include EU expansion towards the east (including to Ukraine), institutional reform to make an enlarged union function better, a plan to organize and finance a common European security and defense policy within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the next seven-year budget for the period after 2027. Weak governments in France and Germany bode ill for EU progress on any of those issues.

More on:

Neither the far-left nor the far-right propose leaving the European Union; instead, they want to change the EU from within by clawing back powers from Brussels. They can frustrate the workings of the European Union by halting controversial laws, which would inevitably end up with the EU’s Court of Justice. There is a real risk that a new French government would follow the examples of Hungary and more recently the Netherlands by choosing to opt-out from certain European policies, including those on immigration and national procurement, which would have a direct impact on the border-free Schengen area and the single market. If the far-right seeks to reinstate the primacy of French law over EU law, it is bound to clash with the other EU member states, and the European legal order will start to look increasingly shaky. And if France is no longer willing to follow EU rules or faithfully implement decisions taken by the European Council of Ministers, then it is doubtful that the EU can continue to function as it has for the past few decades.

Which concerns of French voters could be decisive?

The issues that will propel French voters toward the polling booths on Sunday include social and economic matters as well as immigration. Social issues of concern include declining purchasing power, the future of social security, and rising income and wealth inequality. One of the most important economic issues is the lack of growth: in 2023, gross domestic product (GDP) growth slowed to 0.7 percent, and it is now expected to be slightly below that in 2024. Then there are the growing levels of debt and deficits. The French deficit is structural, at 5.5 percent of its GDP in 2023 and expected to reach 5.3 percent in 2024, in violation of the EU’s Stability and Growth pact, that requires France to steadily reduce its deficit to below 3 percent. National debt is expected to grow from 110.6 percent of GDP in 2023 to 113.8 percent in 2025. While the far-left tends to do well with voters worried about social issues, the far-right is trusted more to deal with economic issues and to impose tough policies to curb the influx of illegal immigration.

While turnout in presidential contests tends to be quite high, at 70–80 percent, voter participation is often much lower for legislative elections (which usually follow right after presidential elections), hovering near 40–50 percent in the last fifteen years. Pollsters and analysts expect the legislative elections on June 30 and July 7 to have a higher turnout given how much is at stake and Macron’s dramatic call for clarity in French politics. So, though hard to predict in exact terms, turnout could be anywhere between 60 and 70 percent—higher than most other legislative elections, but probably lower than presidential ones, given voter fatigue and the abrupt timing of the elections. Many college students will still be in the middle of final exams during the voting.

Opinion polls show Bardella’s far-right National Rally in the lead, with about 35 percent of the vote. The left-wing New Popular Front, which has yet to pick a leader and candidate for prime minister, follows at around 28 percent. Macron’s centrist bloc Ensemble (“Together”), led by current Prime Minister Gabriel Attal, trails far behind at 20 percent. If those results roughly hold on Sunday, Macron-backed candidates are unlikely to contest many seats in the second round, which is likely to be a straight-out contest between the united left and the far-right. Indeed, Macron’s Ensemble is at risk of going from 245 seats to less than 100 in the next Assembly.

If a right-wing alliance led by National Rally wins, is cohabitation possible with President Macron?

Since Charles de Gaulle founded the Fifth Republic in 1958, there have only been three cohabitations. The first was between Socialist President François Mitterrand and Gaullist Prime Minister Jacques Chirac from 1986 to 1988. The second one consisted of Mitterrand and conservative Prime Minister Edouard Balladur, from 1993 to 1995. The longest one was between Gaullist center-right President Jacques Chirac and socialist Prime Minister Lionel Jospin, from 1997 to 2002. While there is always a risk of political paralysis in such arrangements, centrist presidents and prime ministers have found ways to make it work, even despite occasional awkward situations, such as when Chirac and Jospin both insisted on having a chair at international summit meetings.

If the far-right National Rally wins an outright majority or manages to make a governing coalition with the center-right Republicans, Macron will have no choice but to appoint Bardella as prime minister and have him form a government. Macron can still chair the cabinet meetings, but in practice, he will not hold the same sway over them as he would if his party and legislators controlled the National Assembly. Macron will have the power of “nuisance,” meaning he can frustrate the government by refusing to sign decrees and ordinances. He can also dissolve parliament, though he will have to wait at least a year to do so, and there is always a risk of such a move backfiring by giving the government an even bigger majority.

The French elections are the first of three involving pillars of the transatlantic alliance of France, the United States, and the United Kingdom (UK). Will the French vote be a harbinger of any broader changes going on in the United States and UK?

It is quite striking that all three prototypes of modern systems of democratic government—the U.S. presidential system, the UK parliamentary system, and the French semi-presidential system—could experience major political transformations within the span of six months. The UK is on the cusp of ending fourteen years of often-chaotic Conservative government by voting in a Labour government led by Keir Starmer on July 4, while the United States will decide on November 5 whether to bring back the also-chaotic presidency of Donald Trump. If elected, Trump could further erode democratic norms such as the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary.

France’s potential experiment with a far-right government checked by a centrist president is not a harbinger of broader changes occurring in the other countries, despite the similar voter dynamics at play in all three. These include concerns about the rising cost of living, growing anti-immigration sentiment, and a weariness with the many policies to fight climate change, including the switch to renewables and the imposition of environmental regulations in the agricultural sector. All three countries similarly manifest voting patterns that divide the population among urban-rural, class, and generational lines. The main factor uniting all three, however, is a clear anti-incumbent sentiment, which does not bode well for U.S. President Joe Biden’s chances of reelection over Donald Trump this fall.

Online Store

Online Store