The Time of the Kurds

Despite a history marked by marginalization and persecution, many Kurds hold onto hope of achieving their people’s century-old quest for independence. How have they been shaped by their struggle?

This infoguide is now archived.

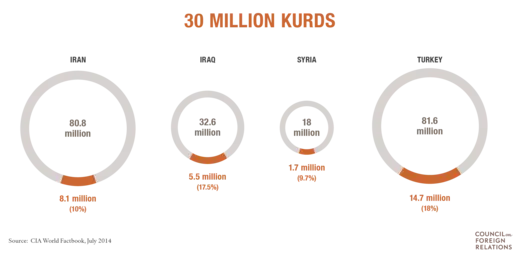

The Kurds are one of the world’s largest peoples without a state, making up sizable minorities in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. Their history is marked by marginalization and persecution. Yet some Kurds may be on the verge of achieving their century-old quest for independence in a Middle East undergoing the convulsions of Syria’s civil war, Iraq’s destabilization, and conflict with the self-proclaimed Islamic State.

Who Are the Kurds?

The Kurds are one of the indigenous peoples of the Middle East and the region’s fourth-largest ethnic group. They speak Kurdish, an Indo-European language, and are predominantly Sunni Muslims. Kurds have a distinct culture, traditional dress, and holidays, including Nowruz, the springtime New Year festival that is also celebrated by Iranians and others who use the Persian calendar. Kurdish nationalism emerged during the twentieth century following the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the formation of new nation-states across the Middle East.

The estimated thirty million Kurds reside primarily in mountainous regions of present-day Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey and remain one of the world’s largest peoples without a sovereign state. The Kurds are not monolithic, however, and tribal identities and political interests often supersede a unifying national allegiance. Some Kurds, particularly those who have migrated to urban centers, such as Istanbul, Damascus, and Tehran, have integrated and assimilated, while many who remain in their ancestral lands maintain a strong sense of a distinctly Kurdish identity. The Kurdish diaspora of an estimated two million is concentrated primarily in Europe.

Kurds have a long history of marginalization and persecution, and, particularly in Iraq and Turkey, have repeatedly risen up to seek greater autonomy or complete independence.

We have to rectify the history of mistreatment of our people and those who are saying that independence is not good. Our question to them is, if it’s not good for us, why is it good for you?

At the outset of the twenty-first century they have achieved their greatest international prominence yet, most notably in Iraq. Iraqi Kurds were an important partner for the U.S.-led coalition that ousted Saddam Hussein from power in 2003. After more than a decade of serving as the “glue” that holds the country together amid sectarian tensions between Sunni and Shia Arabs, Iraqi Kurds are increasingly asserting their autonomy and charting a path toward independence.

The Iraqi Kurdish fighting force, known as peshmerga (Kurdish for “those who face death”), and Syrian Kurdish fighters have played a significant role in fighting the self-proclaimed Islamic State. Other Kurdish fighters, including Turkish guerrilla fighters of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated terrorist organization, have also thwarted Islamic State advances in the region. Meanwhile, efforts by the Turkish government and the PKK to resolve their thirty-year conflict through a negotiated peace process have faltered and a thirty-month cease-fire broke down in 2015. Three thousand people, mostly security forces and militants, have been killed in the Turkey-PKK conflict since then. Southeastern Turkey has been devastated in the Turkish military campaign to drive PKK fighters from cities, while Kurdish militants set off car bombs in Istanbul and Ankara.

The role of Kurdish forces in the fight against the Islamic State in particular has raised their international profile. Some countries, including Germany, have directly armed and trained Iraqi Kurdish forces. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has begun arming Syrian Kurds over Turkey’s objections, expanding the United States’ involvement after years of providing air cover for Kurdish ground operations against the Islamic State.

Multinational Heritage

Four countries are home to large Kurdish minorities, who call the mostly contiguous area they inhabit Kurdistan, or land of the Kurds. In two of these countries, Kurds have established different and separate forms of self-rule.

In Iraq, Kurds primarily reside in three provinces that make up the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Iraqi Kurds have had de facto autonomy since 1991, when a U.S.-led coalition established a no-fly zone over Kurdish areas to protect them from Saddam Hussein’s attacks. The KRG was officially recognized as a semiautonomous region in the 2005 Iraqi constitution, following the U.S. invasion of Iraq and fall of Saddam's regime two years earlier.

Some Iraqi Kurds live outside of the KRG, however, and the Kurds have laid claims to areas outside their recognized borders, including the contiguous oil-rich Kirkuk region. Kurdish leaders refer to the city of Kirkuk, located about sixty miles from the Iraqi Kurdish regional capital of Erbil, as their Jerusalem, alluding to the city’s disputed status among different ethnic groups decades after Saddam ousted thousands of Kurds and resettled the region as part of his “Arabization program.” Kirkuk has been the focal point of the Kurds’ disputes with Baghdad over territory and resources, with the region potentially contributing about half of the oil exported from the KRG. The Iraqi military fled the area in the face of Islamic State fighters’ advances in 2014, but peshmerga forces deployed against the insurgents were later able to retake control of Kirkuk. Kurdish rule has created a fragile peace, but efforts to reverse the Arabization of the region, which include the intimidation and forced displacement of some Sunni Arab residents, have raised tensions. Continued Kurdish control of the city, along with the solidifying positions of Shia militias to the south and west of Kirkuk city, may define the future status of these contested areas.

In northern Syria, Kurds inhabit two noncontiguous regions, which also have oil deposits, near the borders with Turkey and Iraq. Amid the Syrian civil war, Kurds declared self-rule in 2012 and have since expanded their territory as they defeated Islamic State forces, with crucial support from the U.S.-led coalition. Turkey, concerned that Syrian Kurds linked to the PKK have permitted the outlawed group to establish bases along its southern border, has increased support to Arab rebel groups in the region in order to prevent Kurds there from unifying the two cantons. It deployed troops to northern Syria in 2016 to halt the Kurdish advance, adding complexity to that conflict as the United States tried to keep its various partners focused on defeating the Islamic State in its self-made capital, Raqqa.

Historical Context

Since the fall of the Ottoman Empire dispersed Kurds into four nations nearly a century ago, they have pursued recognition, political rights, autonomy, and independence. Throughout this period, Kurds have been persecuted, Kurdish identity has been denied, and thousands of Kurds have been killed. In each of the four nations, Kurds have had uneasy relationships with authorities, at times rebelling and at other times cutting deals with the governments. The destabilization of Iraq, civil war in Syria, and the rise, and collapse, of the Islamic State present new challenges, but also opportunities, for the Kurds.

The Kurd’s Long Struggle With Statelessness

Independence and Disunity

The quest for independence is intrinsic to Kurdish identity. However, not all Kurds envision a unified Kurdistan that would span the Kurdish regions of all four countries. Most Kurdish movements and political parties are focused on the concerns and the autonomy or independence of Kurds in their specific countries. Within each country, there are also Kurds who have assimilated, and whose aspirations may be limited to greater cultural freedoms and political recognition.

Kurds throughout the region have vigorously pursued their goals through a multitude of groups. While some Kurds established legitimate political parties and organizations in efforts to promote Kurdish rights and freedom, others have waged armed struggles. Some, like the Turkish PKK, employed guerrilla tactics as well as terror attacks on civilians, including fellow Kurds.

The wide array of Kurdish political parties and groups reflects the internal divisions among Kurds, which often follow tribal, linguistic, and national fault lines, in addition to political disagreements and rivalries. Tensions between the two dominant Iraqi Kurdish political parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), escalated to a civil war that killed more than two thousand Kurds in the mid-1990s.

Political disunity stretches across borders as well, with Kurdish parties and organizations forming offshoots or forging alliances in neighboring countries. Today, disagreement over the prospects for Kurdish autonomy in Syria or Iraqi Kurds’ relations with the Turkish government fosters tensions that have pitted the Iraqi KDP and its Syrian sister organization, the KDP-S, against the PKK and its Syrian offshoot, the PYD. Still, adversarial Kurdish groups have worked together when it has been expedient. The threat posed by the Islamic State has led KDP-affiliated peshmerga to fight alongside Syrian PYD forces.

Kurdish groups have at times bargained with not only their own governments but also neighboring ones, in some cases at the expense of their relations with their Kurdish brethren. The complex relationships among Kurdish groups and between the Kurds and the region’s governments have fluctuated, and alliances have formed and faltered as political conditions have changed. The Kurds’ disunity is cited by experts as one of the primary causes for their inability to form a state of their own. Another is that as a landlocked people they are reliant on governments that oppose their independence.

Kurds in the Emerging Middle East

Domestic upheaval and political changes throughout the region have made Kurds critical players on many fronts, particularly in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey.

In Iraq, sectarian conflict between Sunni and Shia Arabs threatens the country’s unity even as the Islamic State’s control recedes. The Kurdish region has been largely unharmed by the sectarian fighting, and Kurdish peshmerga forces halted the initial advance of Islamic State militants into their autonomous region. Amid the fighting, the Kurds deployed forces farther south, filling the void left by the retreating Iraqi military. The Kurds have taken control of Kirkuk, an oil-rich region to which they have long laid claim. Tensions between Erbil and Baghdad peaked in 2014 over oil-revenue sharing between the regional and federal governments. Though resolved later that year, the dispute exposed a widening rift.

Their dispute came to a head in September 2017, when the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) held a referendum on independence, extending voting to Kirkuk city and governorate as well. Iraq’s neighbors opposed the referendum, fearing that Iraqi Kurdish independence would inspire their own Kurdish minorities to seek autonomy. The move was also denounced by the United States and other Western powers, which have spent hundreds of billions of dollars and lost thousands of lives trying to keep Iraq unified. Some Iraqi Kurdish groups oppose it as well, fearing that an independent Kurdistan would perpetuate KRG President Masoud Barzani’s rule. The measure passed overwhelmingly, which Barzani believed would give him a strong hand to negotiate over boundaries and resources. While Baghdad has refused talks and demanded that the referendum be annulled, Kurdish officials have not made any unilateral moves toward independence.

In Syria, civil war between the Assad regime and its supporters and myriad antigovernment groups has killed more than 320,000. The Islamic State, which is fighting against both government and antigovernment forces, controls territory in the north and the east. The Kurds have not taken a side in the civil war but, filling the void after Syrian government forces left the area, have established self-rule in two regions. The PYD has governed since mid-2012, and its military arm, the People’s Protection Unit (YPG) has been fighting against the Islamic State, with support from U.S.-led air strikes. The coalition’s support for the PKK-affiliated group has caused tensions between the United States and Turkey, a NATO ally. As the major component of a mostly Kurdish fighting force known as the Syrian Democratic Forces, the YPG has made significant gains since expelling the Islamic State from the northern Syrian town of Kobani in 2014 and raced to consolidate its territory and capture Raqqa in 2017. Rights groups have compiled evidence of Kurdish efforts to alter the demographics of the captured territories, including the razing of some Arab villages.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s negotiations with the PKK and its jailed leader, Abdullah Ocalan, to end the insurgency, which has killed forty thousand people since 1984, have ended, and along with it a cease-fire that brought calm to Kurdish-majority regions in the southeast. The ruling AKP shifted away from aiming to integrate Kurds into Turkish society—ending a ban on broadcasting and teaching in the Kurdish language—to courting Turkish ultranationalists and seeking to expand the powers of the presidency, held by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The HDP, a pro-Kurdish party, played a role as mediator in the peace process, but its leaders and thousands of its members have since been jailed over alleged ties to militants.

Iran’s Kurds have received less international attention than their Iraqi, Syrian, and Turkish brethren. Experts attribute this partly to internal disunity, but mostly to the Iranian regime’s political repression and limits on international media coverage. In 2011, the government carried out a massive military campaign against the Kurdish guerrilla group Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan (PJAK), which left hundreds dead, including civilians. Iran has routinely executed Kurdish activists.

Every day the regime is killing our people for nothing other than seeking their rights, and the world remains silent.

Flashpoints

Conflict fracturing two countries, a delicate normalization process in a third, and Kurdish nationalist aspirations could reshape the Middle East and trigger further upheaval. Experts point to three unfolding developments that could significantly affect the Kurds and the region.

Iraqi Kurdish Independence

A September 2017 referendum on independence that was overwhelmingly backed by Iraqi Kurdish voters has raised tensions between Erbil and Baghdad. While the Kurdish government has framed the vote as a mandate to negotiate with Baghdad over the terms of separation, President Haider al-Abadi has instead demanded that the referendum be annulled and threatened to isolate the landlocked region. A move toward independence would also risk conflict with Iran-backed Shia militias and possibly even inflame the sectarian competition between Iraq’s Sunni and Shia Arabs.

Neighboring Iran, Syria, and Turkey are concerned that independence for Iraq’s Kurds could inspire uprisings in their own countries and that an independent Iraqi Kurdistan might harbor militants. Under Erdogan, Turkey has forged extensive economic ties with the KRG, including a booming oil trade, but also targeted PKK posts in KRG territory in 2017. After the referendum it threatened to shut down an oil pipeline on which the KRG relies.

International support is seen as critical to the viability of an independent Kurdistan since it would be landlocked and reliant on its neighbors for the passage of goods and people. Iraqi Kurds moved forward with the September referendum, experts say, because they fear that U.S. support for them will only dry up as the campaign against the Islamic State winds down. But even so, the United States condemned the referendum, reiterating its commitment to a unified federal Iraq and reflecting the concerns of Turkey, a NATO ally. The European Union, too, called the vote illegitimate. Some countries may also be reluctant to support Kurdish independence due to minority secessionist movements within their own borders.

Iraqi Kurds have claimed disputed territories beyond the borders of the three provinces that make up the Kurdistan Regional Government and where Arabs, Turkmen, and others have lived for many years. Stoking tensions with Baghdad, Kurdish officials extended the referendum to the ethnically mixed, oil-rich Kirkuk area, which the peshmerga captured in 2014 from the Islamic State.

Battling the Islamic State

Kurds in both Iraq and Syria continue to be embroiled in the fight against the Islamic State, but the battle is waning. Thousands of Kurds have been killed in battles that shrunk the Islamic State’s footprint to a fraction of its 2014 peak, a sacrifice which has earned the Kurds a global reputation as the most effective ground forces against the militant group.

The United States has trained Iraqi Kurds and backed Syrian Kurds with airpower, though notably, it has refused to circumvent Baghdad and directly provide arms to the Peshmerga. The U.S. decided to provide weapons to Syrian fighters, angering Turkey, which sees arms provided to the YPG as tantamount to backing the PKK. The Iraqi Kurds have also received training and weapons from European countries, as well as Iran. Meanwhile, the PKK has also supported the Syrian Kurds with training, arms, and fighters. Support from foreign powers has also raised concerns in Iraq, which is wary of further empowering its autonomous Kurdish region. As the battle against the Islamic State winds down, Syrian Kurds are expected to reap the spoils, solidifying control over large parts of northern Syria. But their ascendency may end up being short-lived if U.S. support wanes and both Turkey and the Assad regime return their focus to thwarting the potential for an autonomous Kurdish state.

Turkey-PKK Relations

The fragile peace process between the Turkish government and the outlawed Kurdish insurgent group, the PKK, is broken, and both sides appear entrenched in a violent struggle that most analysts say can’t be resolved militarily. The Turkish army is one of the world’s largest, but Kurdish militias have proven resilient and their fighters, if not their cause, have gained international recognition after successes against the Islamic State. Tensions have been exacerbated by the conflicts in Iraq and Syria. The Turkish military has driven out PKK fighters from urban centers and has targeted the group and other militants in Syria and Iraq, earning rebukes from rights groups for alleged abuses in its domestic operations and from the United States for impeding the campaign against the Islamic State.

The Turkish military’s operations in the southeast destroyed entire districts of major towns in 2016, and the PKK escalated its attacks on Turkish government targets. Advances by U.S.-allied Kurds in northern Syria have given the PKK sanctuary that Ankara intends to eliminate. And with the ruling party’s continued pressure on opposition groups and critical media, there were few signs in mid-2017 that relations will improve and the peace process will be resumed.

Taking the YPG and PYD into consideration in the region will never be accepted and will go against a global agreement that we have reached.

Credits

Executive Producer: Jeremy Sherlick

Assistant Producers: Kevin Lizarazo, Katherine Wise

Graphic Designer: Julia Ro

Online Store

Online Store